MORE than a hundred kids actually gave up the World Cup in favour of dance, can you imagine? There is hope for the arts yet!

The event was Sanggar Koreografi Malaysia 2006, a platform for choreography presented by the Akademi Seni Kebangsaan’s dance department that is headed by the indefatigable Joseph Gonzales.

The event, called ilham, proses, karya (inspiration, process, creation), comprised a weeklong workshop for dance professionals beginning on June 11 at the academy’s campus in Kuala Lumpur and three nights of performances at its Experimental Theatre over the last weekend.

Participants hailed from all over Malaysia as well as the Victorian College of Arts (VCA) in Australia and Institute Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta (ISIY) in Indonesia.

In the heady early days of dance in this country, Malaysian choreographers attempted to fuse various local dance genres (especially classical, traditional and folk dances) with Western ones to create a “contemporary” style. The outcome was awkward and shallow – works that tried too hard to incorporate anything Malaysian.

Looking at the works of the academy’s lecturers and choreographers such as Umesh Shetty (Alla Rip Pu), Wong Kit Yaw (Under the Moonlight), and Zhou Gui Xin (Journey), as well as that of graduate Firdaus Mustapha Kamal (Om Swasti Astu), it is evident that Malaysian choreographers have progressed from merely “fusing” dance genres to reinventing classical, traditional and folk dances. For sure, the shape of “contemporary dance” in Malaysia is emerging, and it is a shape drawn from our own dance traditions.

The performances over the three nights could be loosely categorized into three types: contemporary Asian, thematic, and technical.

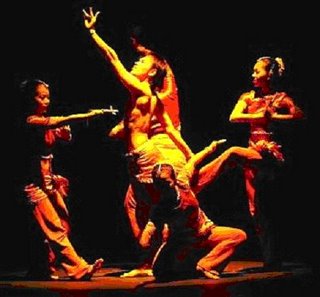

Umesh’s Alla Rip Pu is surely one of his best works. He merged the pure dance style of barathanatyam (allarippu) with contemporary dance. Originally performed by dancers trained in classical Indian dance, this version was performed by dancers who were not. Those who saw the earlier version might agree that the advantage of classical Indian dance training was very clear, but the advantage of this version is that it made barathanatyam accessible to other dancers.

Under the Moonlight by Wong was pure delight despite its done-to-death theme of youth and love. His perception of culture and life is deeply original and his interpretation, fresh. It made me say, “Hey, I’ve never seen it this way before!” Drawing movement vocabulary from Chinese folk dance, he recreated the simple lives of villagers and the vitality and exuberance of youths in love.

Journey by Zhou explored the xin jiang (a type of Chinese dance) style in a dance that portrayed the nomadic journey of a tribe and its quest for a home. The dancers, proud in their smart uniforms, marched to an anthem – grandiose music added to the nationalistic feel. Zhou used minimal movements focused mainly on the hands and upper body and maintained the clean-cut simplicity in formations.

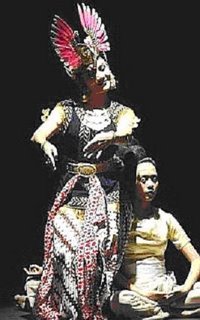

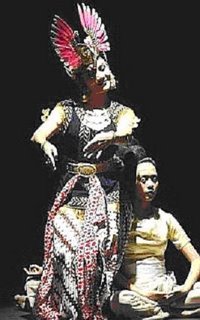

Firdaus’ Om Swasti Astu (“welcome” in Balinese) is a Balinese dance contemporised by reinventing the context while maintaining the movement vocabulary. Originally a war dance (baris, a Balinese warrior dance) performed by a group of men, it was presented as a duet (between a male and female dancer) that told the story of the choreographer’s personal journey in life. And to Firdaus, it seems, life is a road full of battles. The two characters, in sudden and accented movements, nodded their heads violently as if they were having a fierce conversation.

Sonata Borobudur by Hendro Martono of ISIY did not successfully project the splendour of Borobudur (the biggest Hindu-Buddhist temple in Indonesia) and the sad feeling of how it’s degenerated into a tourist attraction did not come through. The pace was also too slow. In the end, it was not choreography but traditional costumes that bound “classical” and “contemporary”.

Two compositions by Suhaimi Magi were presented – Dulang and Paut. Dulang is an exploration of movement that is taken from the vocabulary of tari piring (“saucer dance”, a Malay dance). Far from reflecting a farmer’s daily activities (typical in tari piring), solo dancer Liu Yong Sean looked like he was exploring the many ways with which to play with the metal tray. Lack of direction notwithstanding, he danced it like he meant it – a highly commendable effort.

On the other hand, Paut was a beautiful duet, a love story of a couple never apart. The connection between the couple was symbolised by an umbrella (held by the woman) with a sash (held by the man) tied to it.

Theme, concept or idea-based choreographies were obvious favourites among the choreographers, both local and foreign.

Mew Chang Tsing (ASK lecturer and choreographer) derived her work from the concept of qi (energy) in her work Qi.vi. The idea is to feel the qi and allow the (invisible) energy to move the body. One cannot find qi within a week – and it was obvious that the workshop participants presenting this dance had not.

9 to 5 depicted the hectic and bitchy life of the office. With wigs and wit, this piece by Gonzales (ASK lecturer and choreographer), offered fun and drama.

Angin-Angin by Sukarji Sriman (Indonesian choreographer, now Universiti Malaya lecturer) told of the winds of change. From a serene jungle setting, the dance moved on to concrete pavements. The transition was underlined by the soundscape that began with a Quran recital and then changed to jazzy tunes.

Graduates from ASK who presented their works were Arif Nazri Samsudin (Hai! Kak Long), Siti Ros Ezeeka Rahmat (Kejar), Fairuz Tauhid (Lemak Berjangkit), Sharip Zainal Sagkif Shek (Hitam Putih Kelabu), and Gloria Anak Patie (H...U...J...).

Of these performances, Hitam Putih Kelabu was the most captivating. And Sharip himself composed the mesmerising score that accompanied the dance. In the dance, two dancers dressed in black “flew” gracefully like birds, one behind the other. The dancers in white seemed to be the evil ones and they were envious of the grace exuded by the dancers in black. Is black good and white evil, or vice versa? Sharip left the matter grey.

On the last night, graduates of VCA presented Glimpse (by Yi Zhang), Playmate (by Marisa Wilson), Up to My Eyes (by Holly Durant, Harriet Ritchie and Amber Haines), Parental Guidance Recommended (by Sara Black), Persona (by Suhaili Ahmad Kamil), and 4 Phase (by Anna Smith).

The graduates were here in Malaysia because of the Persona Project initiated by Suhaili Ahmad Kamil, which is part of her Bachelor of Dance (Honours) program at VCA.

It was quite clear in VCA’s works that technique (especially in Persona and 4 Phase) was emphasised more than elements of culture and tradition. Delightful as the themed and character-based choreographies were, they seemed to be a little obsessed with “little girls” (Playmate and Parental Guidance Recommended). Another choreographic direction is the exploration of emotions and how that emotion can be heightened and conveyed through dance; for example, fear in Glimpse and angst in Up to My Eyes. Both were very dark pieces.

After three nights of such diverse dance delights, I must say that Sanggar Koreografi Malaysia 2006 was a great event, one that even suggested Malaysia has the potential to become a centre for international dance education. Kudos to the dance department of ASK.

The event was Sanggar Koreografi Malaysia 2006, a platform for choreography presented by the Akademi Seni Kebangsaan’s dance department that is headed by the indefatigable Joseph Gonzales.

The event, called ilham, proses, karya (inspiration, process, creation), comprised a weeklong workshop for dance professionals beginning on June 11 at the academy’s campus in Kuala Lumpur and three nights of performances at its Experimental Theatre over the last weekend.

Participants hailed from all over Malaysia as well as the Victorian College of Arts (VCA) in Australia and Institute Seni Indonesia Yogyakarta (ISIY) in Indonesia.

In the heady early days of dance in this country, Malaysian choreographers attempted to fuse various local dance genres (especially classical, traditional and folk dances) with Western ones to create a “contemporary” style. The outcome was awkward and shallow – works that tried too hard to incorporate anything Malaysian.

Looking at the works of the academy’s lecturers and choreographers such as Umesh Shetty (Alla Rip Pu), Wong Kit Yaw (Under the Moonlight), and Zhou Gui Xin (Journey), as well as that of graduate Firdaus Mustapha Kamal (Om Swasti Astu), it is evident that Malaysian choreographers have progressed from merely “fusing” dance genres to reinventing classical, traditional and folk dances. For sure, the shape of “contemporary dance” in Malaysia is emerging, and it is a shape drawn from our own dance traditions.

The performances over the three nights could be loosely categorized into three types: contemporary Asian, thematic, and technical.

Umesh’s Alla Rip Pu is surely one of his best works. He merged the pure dance style of barathanatyam (allarippu) with contemporary dance. Originally performed by dancers trained in classical Indian dance, this version was performed by dancers who were not. Those who saw the earlier version might agree that the advantage of classical Indian dance training was very clear, but the advantage of this version is that it made barathanatyam accessible to other dancers.

Under the Moonlight by Wong was pure delight despite its done-to-death theme of youth and love. His perception of culture and life is deeply original and his interpretation, fresh. It made me say, “Hey, I’ve never seen it this way before!” Drawing movement vocabulary from Chinese folk dance, he recreated the simple lives of villagers and the vitality and exuberance of youths in love.

Journey by Zhou explored the xin jiang (a type of Chinese dance) style in a dance that portrayed the nomadic journey of a tribe and its quest for a home. The dancers, proud in their smart uniforms, marched to an anthem – grandiose music added to the nationalistic feel. Zhou used minimal movements focused mainly on the hands and upper body and maintained the clean-cut simplicity in formations.

Firdaus’ Om Swasti Astu (“welcome” in Balinese) is a Balinese dance contemporised by reinventing the context while maintaining the movement vocabulary. Originally a war dance (baris, a Balinese warrior dance) performed by a group of men, it was presented as a duet (between a male and female dancer) that told the story of the choreographer’s personal journey in life. And to Firdaus, it seems, life is a road full of battles. The two characters, in sudden and accented movements, nodded their heads violently as if they were having a fierce conversation.

Sonata Borobudur by Hendro Martono of ISIY did not successfully project the splendour of Borobudur (the biggest Hindu-Buddhist temple in Indonesia) and the sad feeling of how it’s degenerated into a tourist attraction did not come through. The pace was also too slow. In the end, it was not choreography but traditional costumes that bound “classical” and “contemporary”.

Two compositions by Suhaimi Magi were presented – Dulang and Paut. Dulang is an exploration of movement that is taken from the vocabulary of tari piring (“saucer dance”, a Malay dance). Far from reflecting a farmer’s daily activities (typical in tari piring), solo dancer Liu Yong Sean looked like he was exploring the many ways with which to play with the metal tray. Lack of direction notwithstanding, he danced it like he meant it – a highly commendable effort.

On the other hand, Paut was a beautiful duet, a love story of a couple never apart. The connection between the couple was symbolised by an umbrella (held by the woman) with a sash (held by the man) tied to it.

Theme, concept or idea-based choreographies were obvious favourites among the choreographers, both local and foreign.

Mew Chang Tsing (ASK lecturer and choreographer) derived her work from the concept of qi (energy) in her work Qi.vi. The idea is to feel the qi and allow the (invisible) energy to move the body. One cannot find qi within a week – and it was obvious that the workshop participants presenting this dance had not.

9 to 5 depicted the hectic and bitchy life of the office. With wigs and wit, this piece by Gonzales (ASK lecturer and choreographer), offered fun and drama.

Angin-Angin by Sukarji Sriman (Indonesian choreographer, now Universiti Malaya lecturer) told of the winds of change. From a serene jungle setting, the dance moved on to concrete pavements. The transition was underlined by the soundscape that began with a Quran recital and then changed to jazzy tunes.

Graduates from ASK who presented their works were Arif Nazri Samsudin (Hai! Kak Long), Siti Ros Ezeeka Rahmat (Kejar), Fairuz Tauhid (Lemak Berjangkit), Sharip Zainal Sagkif Shek (Hitam Putih Kelabu), and Gloria Anak Patie (H...U...J...).

Of these performances, Hitam Putih Kelabu was the most captivating. And Sharip himself composed the mesmerising score that accompanied the dance. In the dance, two dancers dressed in black “flew” gracefully like birds, one behind the other. The dancers in white seemed to be the evil ones and they were envious of the grace exuded by the dancers in black. Is black good and white evil, or vice versa? Sharip left the matter grey.

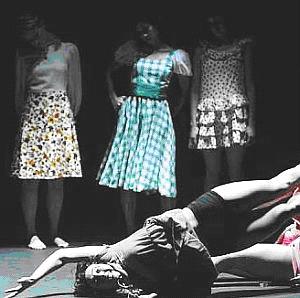

On the last night, graduates of VCA presented Glimpse (by Yi Zhang), Playmate (by Marisa Wilson), Up to My Eyes (by Holly Durant, Harriet Ritchie and Amber Haines), Parental Guidance Recommended (by Sara Black), Persona (by Suhaili Ahmad Kamil), and 4 Phase (by Anna Smith).

The graduates were here in Malaysia because of the Persona Project initiated by Suhaili Ahmad Kamil, which is part of her Bachelor of Dance (Honours) program at VCA.

It was quite clear in VCA’s works that technique (especially in Persona and 4 Phase) was emphasised more than elements of culture and tradition. Delightful as the themed and character-based choreographies were, they seemed to be a little obsessed with “little girls” (Playmate and Parental Guidance Recommended). Another choreographic direction is the exploration of emotions and how that emotion can be heightened and conveyed through dance; for example, fear in Glimpse and angst in Up to My Eyes. Both were very dark pieces.

After three nights of such diverse dance delights, I must say that Sanggar Koreografi Malaysia 2006 was a great event, one that even suggested Malaysia has the potential to become a centre for international dance education. Kudos to the dance department of ASK.