After performing in 40 countries, the company finally arrived on our shores to present its award-winning Hibiki: Resonance from Far Away last weekend at the Kuala Lumpur Performing Arts Centre.

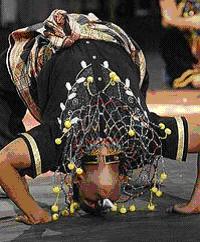

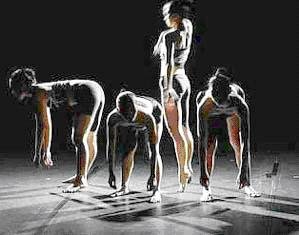

From the first appearance of the dancers, I was held enraptured. They appeared on stage with their bodies painted completely in white, looking identical and surreally ageless. There did not seem to be any reflection of the passage of time on their faces.

According to Ushio Amagatsu, artistic director and founder of the 30-year-old dance company, the life of an individual is “non-continuous”, in the sense that there is a start and an end. But the life of mankind could be described as being continuous, like a flowing river because, as a species, mankind has been alive for centuries and will continue to live. The resonance created by this “non-continuity” and “continuity” is what inspired Hibiki.

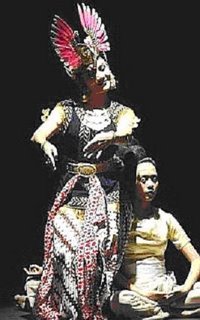

Pix source: Japan Foundation, KL

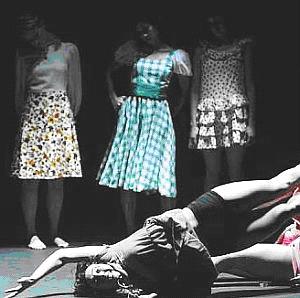

Pix source: Japan Foundation, KL

The six-part dance comprised Sizuku (drop), Utsuri (displacement), Garan (empty space), Outer Limits of the Red, Reflection and Toyomi (resounding).

The first sounds heard in the theatre were “drops of life” – water dripping from suspended glass urns into water-filled concave glass lenses on the sand-covered stage. The set looked like an oasis in the desert; an apt metaphor for Sizuku (drop), which is about the source of life. The first hint of music stirred five figures that had been curled foetally in the spotlight, which was, presumably, the womb.

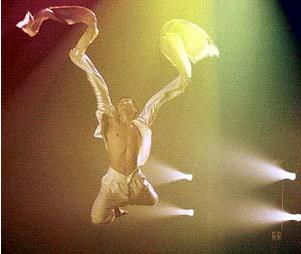

Three dancers remained on the darkened stage in Utsuri (displacement). This segment seemed purposeful and directed with its slow and steady synchronised movements. The dancers’ fingers and hands were always pointing forward; and as they moved forward, they engaged in a triangular love affair with gravity, courting tension, relaxation and resistance.

At some points, the dance seemed to depart from traditional butoh movements (which are slow and very stylised), especially when the dancers started to gyrate and twirl their hands above their heads like Hawaiian hula dancers. Unlike most butoh performances I’ve seen, in which movements are extremely tense, a sense of relaxation permeates Amagatsu’s work.

In the next segment, two dancers entered as asymmetrical dancing twins. They carried out simple, everyday actions – they waved their hands, pointed their index fingers upwards, beat their chests, tapped each other’s shoulders, and so forth. As this duo entered, the earlier trio exited. Action took place at two ends of the stage in this simple, elegant choreographic design.

In Garan (empty space), a solo dancer stood in one spot making slow, miniscule movements; his face serene and his eyes far away. He reached down to dip his finger in the “pool” of water and tasted it. And his reaction seemed to say, “So that’s what life tastes like!” This piece somehow emanated sensations of comfort and security. It put us at ease because, deep in our primal self, we recognised that resonance of life and we are always comfortable with what we know.

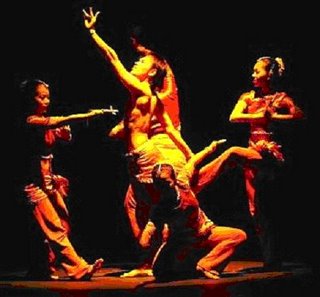

In Outer Limits of the Red, four ghastly figures in crescent formation hovered over a bloody concoction in a glass cauldron. Men in skirts, corsets and earrings muttered spells and flicked “blood” from their hands into the cauldron.

If dance has a horror “genre”, this scene would surely be representative, as it had all the elements of a good horror movie: fear, danger, suspense, shock, and even “bloodshed”. And, yes, it even had a climax, one that made every effort to startle and engage.

Reflection, on the other hand, was anticlimactic. I was at lost trying to understand what the solo performer was trying to convey. The lighting was interesting, though. An “X”-shaped path was “drawn” with orange light across the blue-lit stage and a red “pool” was distinctly marked out by a spotlight.

Toyomi (resounding) paid tribute to birth and the cycle of life. As the dark curtains behind the dancers were drawn away on either side, I felt like a baby witnessing my own birth from inside the womb and seeing light for the first time as my mother’s legs are drawn apart in preparation for my arrival.

And then, in a coda that surely demonstrated the cycle of life, the dance ended as it had begun, with the dancers in the foetal position.

To the thunderous applause of the audience, Amagatsu, in true prima donna fashion, gave us even his bow in butoh style. He can get away with it because, I have to concede, Hibiki was certainly one of the most beautiful butoh choreography I’ve seen.

Pix source: Japan Foundation, KL

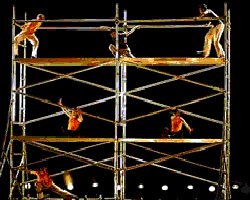

Pix source: Japan Foundation, KL