Pix source: The Star

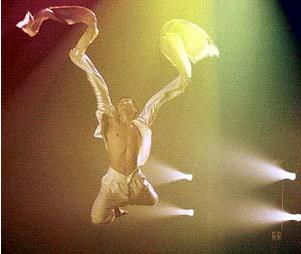

Pix source: The StarJACK Kek Siou Kee performed Dream’n Butterfly, his first solo, to a packed Experimental Theatre at the Kuala Lumpur Performing Arts Centre last weekend. He also did the choreography.

The 29-year-old Trengganu-born lad (who was raised in Kuala Lumpur) was introduced to dance at 19 – he watched Lady White Snake by Mew Chang Tsing, principle of RiverGrass Dance Theatre. The performance spurred him to take up theatre and body movement classes with Woon Fook Sen, a theatre supporter and activist, and subsequently, contemporary and folk dance with Mew.

In 2002, Kek was offered a scholarship to pursue dance studies at the Hong Kong Academy of Performing Arts, where he majored in Chinese dance and took tap and contemporary dance as electives.

“I majored in Chinese dance because as a Malaysian-born Chinese, I want to discover my roots. Hong Kong is the best place for multi-cultural exposure. I learnt a broad scope of Chinese dance encompassing folk, classical and even acrobatics. If I were to study in Beijing, I would have to specialise in one pure Chinese dance style because the schools there follow a very systematic syllabus,” said Kek, who graduated in July this year with a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours) in Dance.

Dream’n Butterfly is a full-length contemporary Chinese dance based on a poem by Zhuang Zhi (369-286BCE), who describes how he dreamt of a butterfly, but woke up wondering if the creature had also dreamt of him.

“When I stand on stage as a performer, I make people believe that I am someone else. Offstage, I’m another person. Who am I? Through this dance, I want to make people wonder the same thing. “I chose this poem because Chinese poets rarely reveal how romantic they are. Most of them write about philosophy. If they do say anything romantic, they would not be so direct “Also, in Chinese culture, the butterfly is symbolic of something significant in life. For me, it’s a dream fulfilled – going to Hong Kong to pursue dance. The lifespan of a butterfly can be as brief as two days; as such, life is very precious and very fragile. I sacrificed all my money and time not knowing what the returns would be. But I really want to do this and I am savouring every moment of my dance pursuit,” Kek added.

Dream’n Butterfly reflects the “it’s-my-last-day-on-earth” attitude that drives him towards excellence.

In the first part of the dance, he portrayed a “man” surrounded by butterflies, as well as a “butterfly”. He toyed with illusion, the way magicians David Blaine and David Copperfield do: without leaving stage, he made both “man” and “butterfly” appear and disappear by interchanging his roles seamlessly.

He fashioned his own butterfly (usually represented by the middle finger touching the thumb with palm facing downwards) using hand gestures. He explored Chao Xian (a type of Korean dance) to depict the starting point of a butterfly’s graceful flutter. He used its breathing techniques to coordinate his body movements as he attempted to follow the erratic flight of the butterfly.

Kek tapped the water (or long) sleeve dance, Han folk dance and Chinese martial arts as the basis for his movement vocabulary. We watched his slow transformation into a butterfly as he first donned a costume with one long sleeve, then a bolero with two long sleeves.

The segment in which he wore one long sleeve was infused with a sense of torment, as if he was lost and unsure about his identity. He wet his sleeves in a makeshift gully filled with water that dripped continuously from the ceiling. He twirled the sleeve to form a “rod”, which he then used to hit several rows of metal rods hanging on the left of the stage, causing them to clash noisily.

The moments of torment passed and he ended with a multimedia segment filled with peaceful images – quite a contrast to the earlier scene. The dancer had found peace with his new identity – a white butterfly.

He assumed this new identity with confidence. With two long sleeves at his disposal, he showed his mastery in the water sleeve style. Like a reptile catching its prey with its tongue, he unfurled his sleeves, then retracted them with lighting speed. He displayed control by using them to form ripples, creating images of water flowing down a stream.

Pix source: The Star

Pix source: The StarOccasionally, his hands created a butterfly that appeared inbetween the panels, or as a shadow behind them. And then Kek, as man or butterfly, left the darkened stage. The butterfly was gone.

Dream’n Butterfly evoked a feeling of the surreal. What’s real is that Kek has proven his mettle in contemporary Chinese dance.