THROW away those racial unity textbooks and pick up performing arts instead. It’s becoming obvious to me that that’s the better way to foster the much-talked-about muhibbah spirit: once you sing it, act it and dance it, you will inherently live it.

At Akademi Seni Budaya dan Warisan Kebangsaan (Aswara), each student is instilled with a thirst for knowledge, the urgency to preserve her cultural heritage, and a deep respect for diversity. It is one of those few places where everyone is genuinely interested in cultures other than their own.

With scant regard for race, religion and background, students from its dance and music departments got together to put up Tapestry 2006, a showcase of Malaysian folk repertoire, at the Experimental Theatre, Aswara campus, Kuala Lumpur, last weekend. The songs and dances were stitched into an evening celebrating Deepavali and Hari Raya.

Eleven dances were presented, many of which are rarely performed in KL. One such is the colourful dansa of the Malay Cocos, who live in Tawau and Eastern Sabah. If not for the hint of batik, one would have thought that this was a Western folk dance.

Performed by couples, it is similar to the European dances of Spain and Portugal in terms of music, costumes and movement, with Spanish melody, lively footwork and loud, frilly blouses worn by both the men and women. Dansa is believed to have been passed on to the local populace by sea-faring tradesmen and travellers.

Another item featured was the rejang be’uh, a Bidayuh dance taken from the village of Semeba, near Kuching. This dance is known for its fast tempo and there was a playful quality between the male and female performers. Many of the movements are derived from daily activities, like imitating birds in flight, as well as footwork that focuses on weight transference.

At Akademi Seni Budaya dan Warisan Kebangsaan (Aswara), each student is instilled with a thirst for knowledge, the urgency to preserve her cultural heritage, and a deep respect for diversity. It is one of those few places where everyone is genuinely interested in cultures other than their own.

With scant regard for race, religion and background, students from its dance and music departments got together to put up Tapestry 2006, a showcase of Malaysian folk repertoire, at the Experimental Theatre, Aswara campus, Kuala Lumpur, last weekend. The songs and dances were stitched into an evening celebrating Deepavali and Hari Raya.

Eleven dances were presented, many of which are rarely performed in KL. One such is the colourful dansa of the Malay Cocos, who live in Tawau and Eastern Sabah. If not for the hint of batik, one would have thought that this was a Western folk dance.

Performed by couples, it is similar to the European dances of Spain and Portugal in terms of music, costumes and movement, with Spanish melody, lively footwork and loud, frilly blouses worn by both the men and women. Dansa is believed to have been passed on to the local populace by sea-faring tradesmen and travellers.

Another item featured was the rejang be’uh, a Bidayuh dance taken from the village of Semeba, near Kuching. This dance is known for its fast tempo and there was a playful quality between the male and female performers. Many of the movements are derived from daily activities, like imitating birds in flight, as well as footwork that focuses on weight transference.

Adai-Adai was originally a Brunei folk song. It tells about life in the fishing villages, where the men leave early in the morning to earn their daily keep and the women folk await their return. Over the years, a new traditional dance has been created to accompany this folk song.

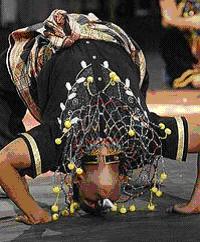

The highlight of the programme was the tari inai, a highly skilled folk form from Pasir Mas, Kelantan. It is a derivative of the mak yong and silat in movement, costume and music. The blare of the serunai (flute) and the delicate fingerwork are strong references to the mak yong tradition, while the swooping hand movements are culled from silat. Also unique in this item was how the dancers bent all the way back to pick up a piece.

Tari Inai. Px Source: The Star

Zapin Bunian, widely performed in Johor, takes its name from the area where it was developed – Kamping Sri Bunian in Pontian. The dance is thought to have been brought to Malaysia by Arab merchants in the 1500s and is synonymous with the spread of Islam. The unique movements of the torso, and the changing rhythms and dynamics of the dance and music make it one of the most exciting folk forms. Originally performed only by male dancers, zapin is now choreographed to accommodate male-female pairs, like in this piece.

Zapin Hanuman was inspired by the Ramayana. Infused with elements taken from the dances of the Middle East, this dance became popular in the 1970s through the work of choreographers such as Syed Hanasuddin and Yahya Abd Hamid. At Tapestry, this item was fast and vigorous – the dancers were practically running, and they performed many turns, hops, and little kicks. It was certainly a test of stamina for them.

The inang renek was choreographed by Wan Nor Mohammad Wan Alam and danced to the tune of Inang Tua. This must be the Malay version of Shakira’s Hips Don’t Lie. This cute and endearing piece saw the dancers take tiny little steps while shaking their hips regularly.

The production also featured two Indian and two Chinese dances.

Veteran classical Indian dancers Radha Shetty and Vatsala Sivadass guided the students in a stunning classical jatiswaram kalyani performance and a spear-bearing Assam dance. Jatiswaram is a pure dance section of the bharatanatyam repertoire, a classical Indian dance form, while Assam is a folk dance from the Indian state of Assam. The latter depicted village men hunting and women tending to their children and farming.

Zapin Hanuman was inspired by the Ramayana. Infused with elements taken from the dances of the Middle East, this dance became popular in the 1970s through the work of choreographers such as Syed Hanasuddin and Yahya Abd Hamid. At Tapestry, this item was fast and vigorous – the dancers were practically running, and they performed many turns, hops, and little kicks. It was certainly a test of stamina for them.

The inang renek was choreographed by Wan Nor Mohammad Wan Alam and danced to the tune of Inang Tua. This must be the Malay version of Shakira’s Hips Don’t Lie. This cute and endearing piece saw the dancers take tiny little steps while shaking their hips regularly.

The production also featured two Indian and two Chinese dances.

Veteran classical Indian dancers Radha Shetty and Vatsala Sivadass guided the students in a stunning classical jatiswaram kalyani performance and a spear-bearing Assam dance. Jatiswaram is a pure dance section of the bharatanatyam repertoire, a classical Indian dance form, while Assam is a folk dance from the Indian state of Assam. The latter depicted village men hunting and women tending to their children and farming.

Assam Dance. Pix source: The Star.

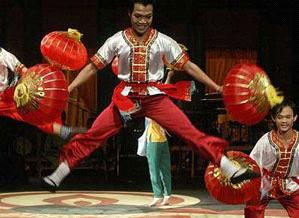

Aswara lecturer Wong Kit Yaw choreographed the Chinese lantern and fan dances. Both pieces manipulated hand-held props to full effect. Wong always makes his work visually appealing; it felt as though I was watching a piece of art take life.

The performance concluded with joget, a folk dance form that is widely regarded as one of Malaysia’s national dances. It is similar to the branyo dance, which has Portuguese origins, due to its distinct time signature and the quick change of weight with the feet. Aris Kadir’s composition had a lively, cheeky quality and was performed by playful partners.

To sum up, Tapestry 2006 displayed the vibrancy of our cultural heritage and a celebration of unity in diversity.